Building social engagement into tailings management

Tailings facility owners are facing the challenge of how to practically integrate social impacts with the systems that manage tailings – as required by the Global Industry Standard for Tailings Management (GISTM). Global engineers and scientists SRK Consulting has proposed a four-step process to achieve this.

The steps cover four key aspects: knowledge sharing, training and awareness; a critical review of systems for gaps and opportunities; upgrading of data systems to highlight targets and trigger action; and strategies for ongoing collaboration and development.

“The importance of social aspects in the GISTM is quite clear,” said SRK Consulting principal environmental consultant Jacky Burke. “It appears as the very first topic in the 2020 publication of the standard, where mines are required to ‘meaningfully engage project-affected people at all phases of the tailings storage facility (TSF) lifecycle’.”

For a start, meaningful engagement requires a range of formalised systems, procedures and monitoring with reference in the GISTM to the mine’s Environmental and Social Management System (ESMS). However, Burke noted that a key hurdle is the typical separation of the more ‘technical’ tailings systems from environmental, social and governance (ESG) systems on most mining sites.

“Mines will generally have an ESMS that operationalises several of the ESG requirements of the GISTM, while there is also a Tailings Management System (TMS) that gives effect to both engineering and governance considerations of the GISTM,” she said. “The current challenge is to integrate the ESMS with the TMS in a way that is practical and effective.”

Integrating social and environmental

Indeed, the ESMS itself has both environmental and social components that need to be integrated with the TMS – the environmental and social components are themselves often not adequately integrated within the mining operation. They are usually managed as separate entities, and often within different departments. While environmental issues may fall under the Safety, Health and Environment (SHE) Department, social management may fall under a Community Engagement or Social Performance Department.

“There are, of course, many different disciplines and skill-sets involved in each function – and each team has its own day-to-day responsibilities and imperatives,” Burke said. “Conformance to the GISTM will require stronger interaction and integration between the range of disciplines and various systems dealing with engineering, social and environmental monitoring, risk management and change management.”

Driving this integration is the growing urgency on the compliance front, as International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) members are working towards a conformance deadline little over a year away. Mines which operate their TSFs with very high or extreme potential consequence ratings must comply with the GISTM by August 2023.

Mind-shift

Key to the essential ‘mind-shift’ which is embodied in the GISTM requirements is to elevate social engagement from being intermittent to being ongoing. Focused engagement is often associated with permitting, as part of the regulatory public participation process during environmental authorisation processes and water use licensing applications.

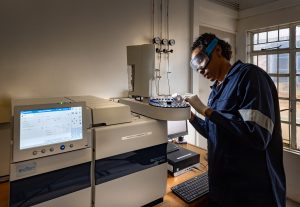

Engagements with affected people should therefore be focused, meaningful and ongoing during the life of the operation and throughout the lifecycle of a TSF – with integration into the regular routines of tailings and environmental management. There is already a greater focus on the importance of environmental and social scientists alongside their engineering colleagues, said Franciska Lake, partner and principal environmental scientist at SRK Consulting. This trend is a positive factor that will facilitate alignment with the GISTM requirements at an operational level.

Informed by risk

This integration of environmental, social and engineering imperatives must, according to the GISTM, be informed by the identified risks. Further, the standard calls for a performance-based monitoring system and governance framework that encompasses both the ESMS and TMS and requires regular review and audit of these systems.

“As the cross-cutting demands of the GISTM may present challenges, the four-step process provides a framework in which mines can structure and evaluate their progress,” said Lake “Importantly, the steps need to be applied iteratively throughout the life of the tailings facility; adaptation will be ongoing supporting effective implementation of the GISTM.”

The first proposed step is concerned with knowledge sharing, training and awareness of a mine’s environmental, social and tailings management teams. The aim is to build mutual understanding among the respective experts on their roles and functions within the site-specific context of their operation and the risks that these pose.

Finding opportunities

“It is therefore critical that this first step involves tailings engineers and operators in collaboration with environment and social management personnel – to facilitate the integration process,” said Lake. “This collaborative group needs to share how site-specific risks are currently being dealt with by the ESMS and TMS, and find opportunities to engage affected people on identified tailings facilities.”

The second step of the process lays the groundwork for the mines to comply with the GISTM requirements through reviews and internal audits. It conducts a critical review of the ESMS and TMS, looks at specific areas for improvement and integration, and identifies gaps in its conformance with the GISTM.

Assess and report

This underpins the third step, where data management systems can be upgraded to facilitate integrated assessment and reporting. The system will set performance targets, and trigger action if these are not met. Along with specifying responsible people for each variable being monitored, the system would also need to include reporting frameworks and schedules in line with what the GISTM requires.

“The fourth step in the process is ongoing collaboration and development, which could involve regular meetings of a forum of GISTM disciplines on the mine,” said Burke. “This forum shares lessons learnt, and keeps everyone informed of risks and corrective actions.”

Lake acknowledged that applying the four-step approach demanded considerable effort and commitment by mine personnel, especially being an iterative process where adaptation and adjustment would always be required. With the GISTM firmly embraced by the sector, and with investors and regulators alike watching its implementation closely, it is vital that mines invest the necessary resources and time to ensure conformance to the GISTM.

Share this content: