SA is letting mining’s next biggest thing slip from its grasp

Andrew Trahar (right) & Brian Menell

IF the world really puts its back into meeting the Paris Agreement goals of net zero carbon emissions by 2050, it will consume six times more critical minerals than today in electric vehicles and power generation, according to the International Energy Agency. These critical minerals include copper, zinc, lithium, graphite, manganese, cobalt, chromium and rare earths.

This should present a great opportunity for countries like South Africa that possess several of these minerals – including a dominant position in global manganese resources.

According to a Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies (TIPS) study dated March 2021 into South Africa’s potential to participate in the lithium-ion battery chain, the country in 2016 was one of the top miners of cobalt (2 300t, as a by-product of platinum group metal (PGM) mining); the world’s largest producer of manganese, with 34% of global production; and the ninth-largest producer of nickel (49 000t, largely a byproduct of PGMs). It also has 2% of global phosphate reserves and 5% of titanium reserves.

According to the Minerals Council of South Africa’s latest Facts & Figures booklet, early indications are that fixed investment in mining stagnated in 2022. Although it may rise in 2023 from self-generation projects, this is “stay in business” investment, not capacity expansion. Exploration spending in South Africa in 2022 was only 9% of its 1990 and 2006 peaks. This spending was mainly on brownfields, not greenfields exploration, the Council said.

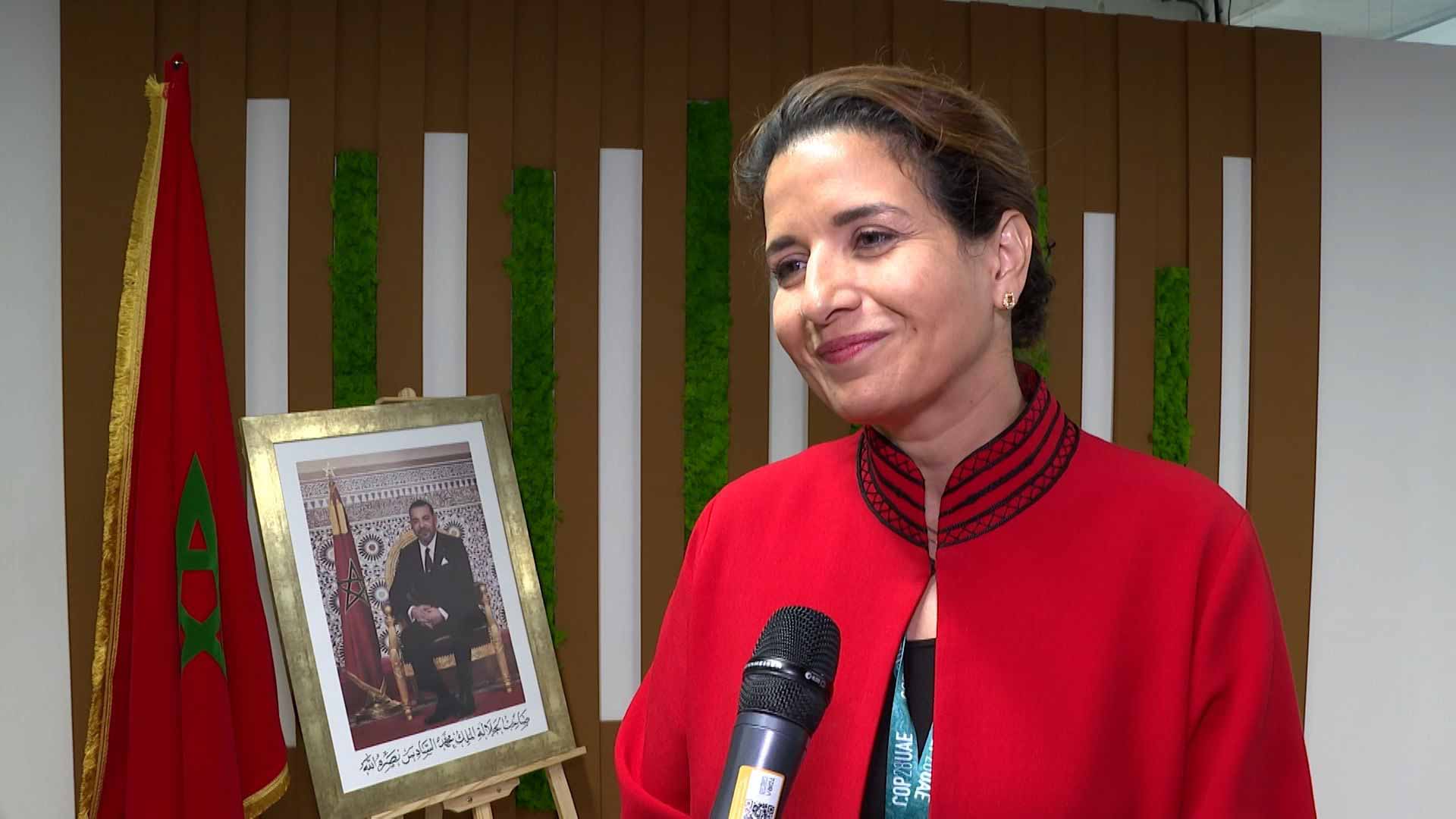

Two veterans of South Africa’s mining industry, now heading global investor groups seeking critical minerals opportunities, are Sir Mick Davis and Brian Menell. They take a slightly different view of the country’s attractiveness.

Brian Menell and his brother Rick sold their family share in Anglovaal Group, which was established by their grandfather, to Anglo American plc in 2001. In 2017, Brian Menell established TechMet. TechMet invests in both upstream (extraction and processing) and downstream (manufacturing and recycling) of critical minerals.

TechMet is targeting lithium, cobalt, nickel, vanadium, rare earth metals, tin and tungsten. Its major shareholders include Mercuria and the US International Development Finance Corporation. Its investments are located in areas that are aligned with the US and its allies.

In South Africa, TechMet holds an interest in Rainbow Rare Earths, which plans to extract rare earth minerals from historic tailings in Phalaborwa. Also in Africa, it owns Trinity Metals in Rwanda, which has six tin and tungsten mines. Trinity Metals employs 5,500 people, making it the country’s biggest miner and biggest private sector employer.

“Rwanda has successfully created quite a disciplined, safe and non-corrupt environment. It isn’t always an easy country to operate in, there is a lot of troubled history, but there is government and organisational discipline, which helps a lot,” Menell said. As for South Africa, his enthusiasm is qualified.

The country isn’t rich in some of the poster minerals of decarbonisation such as copper and cobalt, although it does have major resources of manganese, which when converted into high-purity manganese sulphate, is a key mineral in lithium-ion battery manufacture.

South Africa also has resources of vanadium, which will become relevant in energy storage as the technology evolves. Its dominance in PGMs is well known.

But in order to capitalise on these natural advantages the country needs to attract investment – an obvious, often-heard complaint about South Africa. The regulatory environment needs to be comparable with peer group nations. To its credit, infrastructure and expertise are available but more could be done. “South Africa presents challenges in all these areas, but it is not unique in that respect,” says Menell.

Rwanda has successfully created quite a disciplined, safe and non-corrupt environment. It isn’t always an easy country to operate in, there is a lot of troubled history, but there is government and organisational discipline, which helps a lot – Brian Menell.

“There is a tendency to say: ‘power generation and labour and security and government regulation are all terrible so South Africa is a high-risk problematic environment’. That doesn’t reflect a fair comparison of the absolute risks and challenges in South Africa against other jurisdictions,”he adds.

“Certainly, these are issues, but you can deal with most of them. I am not negative about South Africa. For the right projects, with the right partners, you can still create value in South Africa.”

Menell said doing business in any country – whether it is South Africa, Brazil, Australia, Canada or Indonesia – is a matter of familiarity, knowledge, networks and being able to assess and manage risk to realise value from investments.

“We are open to the possibility of making other investments in South Africa. We do not do pure exploration, but will invest in projects from those that have a defined, discovered resource and at least a prefeasibility study, through to assets in production with expansion potential.”

Hurdles to investment

Davis is much more critical of where South Africa has landed after offering enormous promise post its first democratic elections in 1994. He was CFO of Eskom in 1993 before becoming CFO of Billiton and then founding CEO of Xstrata, which he built into a $60bn juggernaut until its takeover by Glencore. Vision Blue Resources was founded in 2020 with the intention of capitalising on critical minerals demand. Investments include Kazakhstan’s Ferro-Alloy Resources Group, and NextSource Minerals, a graphite mine in Madagascar. He once considered building a battery anode factory in South Africa but opted for Mauritius.

“We have an interest in investing in appropriate projects that produce minerals for battery storage and there are such potential projects in South Africa,” says Davis.

“South Africa has significant minerals, and it has some competitive advantages in terms of the range of minerals it has. As an investor, you will go where you can find a good project, to tap into a low-cost, appropriate-scale resource. But an environment conducive for investment in South Africa does not exist right now.”

For example, Davis says the proportion of ownership that has to be facilitated for historically disadvantaged groups is a moving target. When ownership changes, the empowerment structure has to be created again. “You can do it once, but if you have to do it again, you cannot work out your investment return and cost of capital.”

If you do not have consistent power at the right rate you cannot build and operate a mine or do any energy-intensive processing. If you cannot get the product from mine to port, you cannot stay in business because you cannot sell it – Mike Davis

South Africa’s workforce is unstable and the infrastructure – power, water, road and rail – is in distress. Government departments are inefficient and unable to deliver regulatory approvals timeously or efficiently.

All this makes it tough to justify investments in hard assets in South Africa, although it may be easier to invest in sectors other than mining, where risks can be managed differently, he says. “If you do not have consistent power at the right rate you cannot build and operate a mine or do any energy-intensive processing.

“If you cannot get the product from mine to port, you cannot stay in business because you cannot sell it. If transport or energy is not available, you have to build your own, which adds to the collateral capital and reduces your returns.

“Having attractive minerals is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for investment,” he says.

As a fixed investment, a mine requires stability first and foremost. This condition applies in every direction, from the regulatory environment to the relationship with the mine’s labour as well as the surrounding community. The list goes on.

“To start with, you want to be sure that you hold valid title and that you will retain that title. You want to make sure that there is a defined agreement on what you will earn on that resource against what government and local authorities earn – in other words, you need certainty on your share of the rent.

“You want to know that the regulations to support communities and other empowerment initiatives are predictable and won’t change. You also want to know you have access to a workforce that is qualified and competent; that you can form a relationship with them, they will turn up for work and that your business will not become collateral damage as they express their dissatisfaction with external issues.

Quiet before the storm

Speaking in broad market terms, Menell is enormously optimistic about TechMet’s opportunities, largely as a result of the supply deficit. “If Tesla is to reach 20 million electric vehicles a year by 2030 that will require two times the current lithium annually mined supply,” he said in June at the Mining Indaba conference. “That is before GM, Ford and VW [EV production] and before the Chinese, which already produced two-thirds of the world’s EV batteries.”

Menell believes that in this context there is no shortage of attractively priced assets in which to invest. “There is a lull in the artificially depressed market at the moment before a 10-year bull run,” he says.

Bank of America said in a report in May that metal inventories were depleted across trading exchanges and in the supply chain notwithstanding weak underlying demand. “Consumers are wary of being caught short,” the bank says. “Copper inventories look critically low and our forecast supply surplus for 2023 has all but disappeared.”

“Automakers will say, I read everywhere I should be using 90kg of copper for a car; right engineers, how do I use 50kg or 60kg? – George Cheveley.

VisionBlue co-founder Andrew Trahar says there is “genuine panic” among automakers but he adds a nuance that it’s not for all metals. In fact, he thinks the projected world copper shortage should not be the proxy of metal supply into the energy transition business. He told the London Indaba that having ‘chaperoned’ the company’s graphite investment in meetings with automakers there was enormous interest in having those meetings. “It was genuine panic for graphite, some cobalt and genuine panic for nickel.”

Not all buy into this notion. George Cheveley, the London-based portfolio manager for asset manager Ninety One, says miners and their backers should guard against “calling that the sky is going to fall in” on the supply and demand. The divide between copper supply and demand was been fairly consistent over the past 20 years, he says.

Alarmism will give pause on the demand side to take appropriate action. “Automakers will say, I read everywhere I should be using 90kg of copper for a car; right engineers, how do I use 50kg or 60kg?” Mining companies “spent big” in 2010, only for the iron ore market to crash. “It’s scary for investors because they remember that; people lost their jobs.”

This article first appeared in The Mining Yearbook

Share this content: