Middlemen siphon billions from war-ravaged DRC’s cobalt, coltan trade

UN troops at Goma in this file photo. Credit: MONUSCO Photos, CC BY-SA 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Middlemen and local militias steal billions from the Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC) cobalt and coltan trade, fuelling conflict and leaving the nation poor, according to a political analyst.

The DRC produces 70% of the world’s cobalt, yet nearly $1 billion vanishes from the legal supply chain each year, according to Oluwole Ojewale, regional coordinator for the Johannesburg-based Institute for Security Studies. Artisanal miners — 150,000 to 200,000 strong, with another million people depending on their work — extract minerals from remote sites in the central African country’s North and South Kivu provinces.

The region erupted into international attention in January after rebel group M23, backed by neighbouring Rwanda, seized the area’s largest city, Goma. Now they’re advancing on Bukavu, 200 km south in South Kivu with its coltan, gold and tin ore mines. A regional peace conference in Dar es Salaam on the weekend urged direct talks among all parties although the DRC has balked at negotiating with M23.

The fighting has killed thousands and displaced at least 100,000 from camps in the volatile eastern Congo. It’s still suffering a humanitarian crisis more than 20 years after two wars drew in a slew of countries and killed some 5 million people, including by starvation and disease.

Supply chains

Ojewale’s research since 2021 shows that most foreign companies don’t mine directly. Instead, they buy minerals through grey-area brokers. These middlemen mix illegally sourced minerals with legally certified ones, which harms responsible sourcing and fuels conflict as rival armed groups deploy and tax artisanal miners. The operations taint global supply chains, especially for electric vehicles and renewable energy projects, Ojewale said.

“The absence of a strong government presence means legal and illegal cobalt quickly mingle,” Ojewale said Monday by phone from Dakar, Senegal. “This system channels profit to armed groups and middlemen while depriving the DRC of its rightful revenue.”

These intermediaries create fake traceability documents and bribe border officials in Zambia, Burundi and Tanzania to move the metal. This lets contaminated cobalt and coltan enter global markets in London, Shanghai and North America.

Minerals are not the sole driver of the conflict, he points out, they’re the tinder that ignites deep-seated ethnic identity and economic tensions.

“Long-standing grievances and fierce competition for power and resources are equally to blame,” Ojewale said.

Mpox

The UN Refugee Agency reports that forced displacement will continue in the hardest-hit provinces this year. This will worsen a crisis that affected 27 million people last year. They faced conflict, food shortages, climate shocks, and epidemics. The DRC is the global epicentre of the Mpox outbreak, recording the highest number of cases worldwide, according to the agency.

Ojewale has visited mining sites firsthand. He warns that without strong law enforcement, the country’s mineral wealth will continue to finance conflict.

After 13 South African soldiers as part of a UN peacekeeping force died near Goma in the last two weeks, President Cyril Ramaphosa urged Rwanda to limit its military aid to the M23 rebel group.

Ramaphosa accused the Rwandan Defence Forces of propping up M23. Rwandan President Paul Kagame says the DRC is unable to control the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, a militia linked to the 1994 Rwandan genocide. A one-sided ceasefire declared by the Congo River Alliance—which includes M23—failed to calm the conflict as the Southern African Development Community and the East African Community scrambled to hold Saturday’s peace summit.

Troublesome actors

The International Energy Agency reports that global cobalt demand will quadruple by 2030. This increase is driven by its use in lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles, smartphones and computers. Yet most foreign firms bypass the DRC’s volatile mining zones, opting instead for local middlemen to supply the critical mineral.

These middlemen source minerals from artisanal operations that operate outside state-approved cooperatives. The government tried to help by giving a monopoly on artisanal cobalt to the state-run Entreprise Générale du Cobalt. They also set up regulatory bodies. However, these efforts have failed due to widespread corruption and weak enforcement. As a result, the illegal trade continues to thrive, Ojewale said.

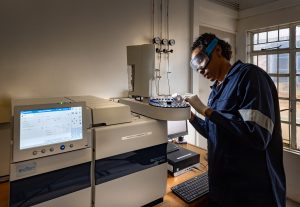

Illegal extraction not only drains billions from the state but also exacts a heavy human and environmental toll. Artisanal miners face dangerous conditions. They often lack protective gear. This exposes them to toxic dust. Toxic dust can cause respiratory diseases, cancer and birth defects. Meanwhile, rampant waste dumping and water contamination destroy local ecosystems and undermine agriculture.

Indaba

The recent Investing in African Mining Indaba in Cape Town discussed the need for artisanal and small-scale operators to become more formalized. This is important because they make a significant contribution to overall mining production each year.

Ojewale stresses that both the DRC and cobalt-importing nations must enforce strict regulations, tighten border controls and improve traceability. The region can only secure its mineral wealth, protect vulnerable communities and stop conflict funding through coordinated action.

“Unless governments and global buyers clamp down on these middlemen, the minerals powering our clean energy future will continue to fund deadly conflicts and rob the DRC of its chance to build a stable, prosperous society,” Ojewale warned.

Share this content: