Kenya’s nascent mining industry set for boom

Mining minister seeks to build additional 10-20 mines in 15 years

Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/5ec41850-2657-11e6-8b18-91555f2f4fde

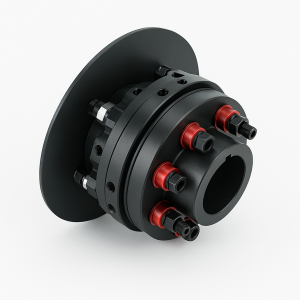

Huge bulldozers pushing tonnes of earth off an escarpment into hoppers at Base Resources’ titanium mine near Kenya’s southern coast look more like remote-controlled toys in a giant’s sandpit than the country’s largest mineral operation. The national picture for the sector is arguably even more gloomy. The $300m facility owned by the Australian and London-listed Base Resources is not only the biggest mine in east Africa’s largest economy, it is the only one of its size. But the landscape appears on the cusp of change. President Uhuru Kenyatta signed a new mining act into law this month that could see Kenya’s nascent mining industry finally come into its own.

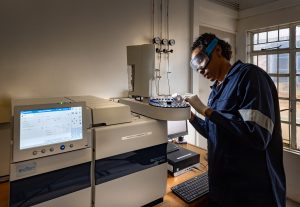

Oil companies, led by the UK’s Tullow Oil, have been prospecting in Kenya for years, and expect to start production by 2021. But with a mining law passed in 1940 and geological data that was often 32 years older than that, Kenya missed out on the mineral exploration boom of the last commodity supercycle that benefited neighbours Tanzania and Uganda. The mining ministry was only created three years ago and the sector’s size is bolstered by the fact it includes production of cement and soda ash. India’s Tata Chemicals part-owns Kenya’s largest manufacturer of soda ash. But Dan Kazungu, the ebullient mining minister, has written a 20-year strategy that he hopes will see up to 20 more operators such as Base Resources in the next 15 years. Government revenues from mining and mineral operations were just Ks1.65bn ($16.5m) in the last financial year. However, Mr Kazungu expects these to have more than doubled by June, the end of the financial year, and has set a goal of 10 per cent of GDP by 2030 — a figure likely to be well over $7bn.

This will be met, he says, by attracting foreign investors, registering the tens of thousands of Kenya’s informal miners — most of whom pan for gold, developing a mining services industry and expanding the small gemstone industry. Western mining executives and analysts say that in addition to gold deposits Kenya has base metals such as copper, rare earth minerals and some coal. Most believe the country does not have the prospects of either Uganda or Tanzania, home to Bulyanhulu, London-listed Acacia Mining’s largest African gold mine. But Mr Kazungu remains optimistic. “We don’t even know what we’ve got,” he says. “About 95 per cent of the rock structures coming up from Tanzania have not even been mapped.” A longer term goal is to make Kenya a regional hub for mining, as it is for financial services. “We should bring minerals here and do value addition,” he says, referring to the processing of raw materials. “About $24bn-worth of minerals go to Thailand each year for value addition and half of that comes from Africa. If we organise ourselves and get even 10 per cent of that, we’ll be making progress.” Related article Global Economy Kenya bucks Africa’s economic trend Tim Carstens, Base Resources’ chief executive who has helped the ministry write its policies and regulations, says the investment climate has already improved. “The steps that were being taken [until last year] were frightening to capital,” he says. “

The noises that are coming out of Kenya now are the soothing noises that investors want to hear. “You can feel we’re in the starting gate. Everyone involved is wanting to get things moving.” Base Titanium, Base Resources’ wholly-owned subsidiary that operates Kwale, has applied to undertake further exploration around its mine; foreign companies are considering prospecting for niobium along the coast; and Acacia, owned by Canada’s Barrick Gold, is among those prospecting for gold — on the Kenyan shores of Lake Victoria. Bulyanhulu is a few hundred kilometres away on the Tanzanian side of the lake and Peter Spora, Acacia’s vice-president for exploration, says he is “cautiously optimistic” about both his company’s prospects and mining in Kenya in general. “Look where Tanzania was in 1999 and 2015 and where Kenya is now,” he says. “I’d say there’s less prospectivity than what we’ve seen in Tanzania but there’s been a lot less exploration so it’s not clear.”

Mr Spora says Mr Kazungu has been “very accessible” and is “going about it the right way” to attract more investment. But, he cautions: “We haven’t seen the final code and we still don’t have the transparency we would like.” Issues such as securing exploration consent and the cost of a mining development agreement are also unresolved. Mr Carstens expects the final regulations to be sufficiently investor friendly to attract new companies but says Mr Kazungu’s targets may be ambitious. “Ten years from discovery to production is fast and there are no advanced big projects in Kenya,” he says. “So we might see two in the next 10 years and perhaps three or four by 2030.”

Share this content:

Post Comment