Maximizing the Benefits of the Renewed Global Interest in Africa’s Strategic Minerals

Negotiations between African governments and foreign investors are often characterized by the various skills, technical capacities, and information asymmetries that shape the balance of power and influence outcomes. The dynamics of these negotiations—in pursuing extractive and infrastructure projects, in particular—merit a special focus, as agreements to carry them out often bind African countries for several decades. Africa is home to a substantial share of the world’s reserves of mineral resources needed for the clean energy transition and could therefore be the main theater for the global race among China, the United States, European countries, Persian Gulf countries, and others to secure access. The International Energy Agency estimates that manufacturers of clean energy technologies will need forty times more lithium, twenty-five times more graphite, and about twenty times more nickel and cobalt in 2040 than in 2020.1

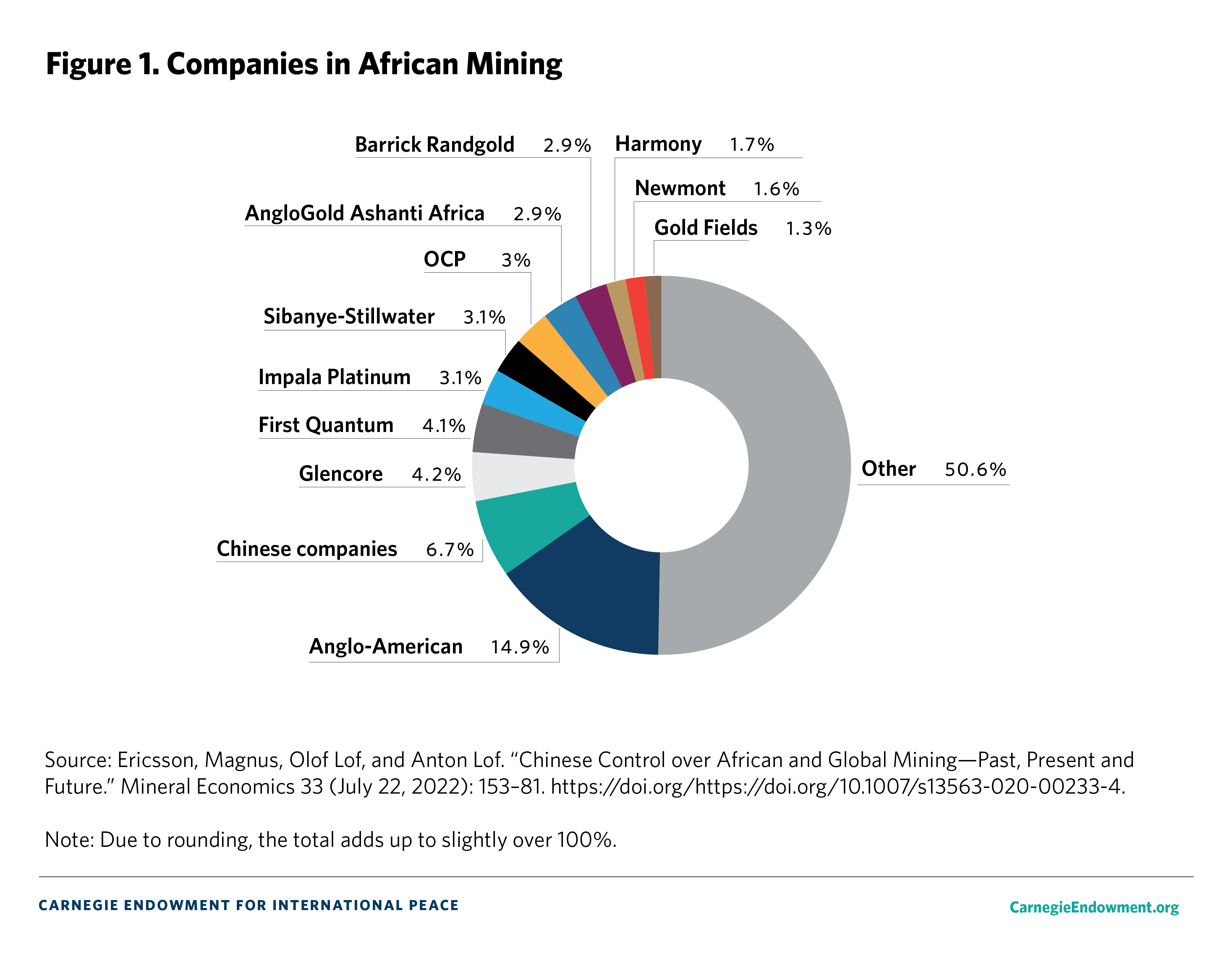

The substantial need for these minerals and metals is increasingly fueling intense geopolitical rivalries in large part because mining negotiations involve more private actors and foreign investors than various other sectors do, such as manufacturing or financial services. In the global race, China appears to be far ahead in building supply chains for cobalt, rare earth minerals, lithium, and several other essential metals and minerals,2 even though mining companies from Europe and North America have a large presence in precious metals and gemstones in many African countries (see Figure 1). Companies from South Africa as well as Morocco also hold minor positions in the global corporate control over African mining.

Chinese companies have emerged as the major players in the mining sector in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Zambia, after decades of dominance by Western multinational companies. Today, the United States has key vulnerabilities in sourcing critical minerals to meet domestic demand for the transition to a low-carbon economy, partly because it is dependent on China for more than half of its supply of twenty-five minerals; and some of these minerals are found in abundance in Africa.3 As countries such as the United States increasingly look to Africa to reduce their vulnerability and dependency, African countries will need to negotiate mining agreements that enable them to retain value from their subsoil resources and further their own countries’ development.

As part of an effort to identify ways in which African stakeholders can maximize the benefits of this renewed interest in the continent’s mineral resources, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Africa Program organized a closed-door workshop in February under the auspices of the 2024 Investing in African Mining Indaba conference in Cape Town, South Africa. The workshop focused on various dimensions of the relationship between governments and investors in negotiating mining agreements for minerals critical to a green, low-carbon transition. The workshop brought together government officials from several African countries; representatives from multilateral organizations and nongovernmental organizations; as well as academics, lawyers that have represented investors’ and/or governments’ interests in the past, and other policy experts to brainstorm and discuss the growing global interest in Africa’s strategic minerals.

The workshop objectives were to share challenges and successes faced during the contract negotiation process for mining deals and to consider how to maximize financial gains, create linkages to the domestic economy, build local supply chains, and comply with labor and environmental standards. The workshop focused specifically on how African governments can best tackle the challenges and harness opportunities during the negotiation process—both from governments’ and investors’ perspectives. Several aspects of the process were covered: for instance, from the governments’ perspectives, how to prioritize policy frameworks and design a national strategy to define the “criticality” of minerals; and from the investors’ perspectives, how to better structure the negotiation process and ensure compliance with strict environment, social, and governance (ESG) standards. Lessons from the experience of other countries, especially Indonesia, were also shared. Finally, the workshop covered the best ways African governments can bridge capacity gaps while dealing with investors and operating at the national and continental levels. Overall, the workshop allowed for candid discussions on how African countries can bolster their agency in the process and how key stakeholders can support the negotiation capacity of African governments.

Government Perspective: Prioritizing Holistic Policy Frameworks

The workshop offered a venue for government representatives to share their past experiences in negotiating mining deals and what they learned from setbacks during the process.

Learning from past setbacks: Several deals were characterized by information asymmetries, opacity,4 environmental concerns, and insufficient provisions to foster the build out of local supply chains to facilitate economic development in the host country. The main overall problem was contract negotiation. African governments often agreed to contracts with a stabilization clause that made them the guarantors of projects and shielded foreign investors from political risk. They often signed these contracts without having all the geological data and statistics of their countries’ mineral reserves, which would then create significant complications down the line among which revenue deficit for the country and difficulties to renegotiate.

Creating adequate policy frameworks: Investors’ increased interest in lithium, cobalt, manganese, graphite, and other minerals presents an opportunity for African countries to take a different approach by first creating a policy framework before signing agreements. According to African government representatives, these policy frameworks should have at least four elements.

First, the framework should clearly articulate the country’s vision for the specific mineral endowment and reflect the decision not to export it as an unprocessed raw product.

Second, it should take a holistic approach to negotiations with investors, including through forming longer-term strategic partnerships, rather than engage in case-by-case negotiations with individual companies. This holistic approach to forming strategic partnerships could include jointly planning endeavors with investors; working with state-owned enterprises, especially on new mining technologies and the easing of transport infrastructure constraints; and working on legislation to enable host governments to set aside certain segments of the project for auction.

Third, the framework should reflect the country’s current geological endowments, as well as up-to-date estimates of the volume and value of mineral deposits. This information will help countries understand whether the reserves are sufficient to support the build out of domestic processing facilities or whether they may be better suited for exports. The case of Guinea was cited as an example of a country that utilized the knowledge of its large iron ore reserves potential to communicate to investors the government’s unwillingness to export the unprocessed commodity.

Finally, the framework should help ensure that legislation and laws on various aspects of the mining sector all contribute to achieving the country’s larger objectives in the sector. Already, countries have various legislations that stipulate (1) consultation with local communities, (2) development of an environmental management plan and labor plan, (3) establishment of a fiscal regime that spells out taxes and royalties, indigenization, and the percentage of local content in employment. These should be better enforced.

Designing a national strategy to avoid fragmented negotiations: Negotiation requires patience, time, and coordination to avoid fragmentation. One way of avoiding this fragmentation is to refrain from hastily signing memorandums of understanding (MoUs) that are not linked to the country’s broader national strategy. Setting a policy framework before negotiating individual contracts and signing agreements is an important recommendation that came out of the workshop discussions. The ultimate objective of this overarching policy framework should be for African governments to be able to eventually participate and domesticate segments of the mining value chain from extraction to processing, to refining, and to downstream manufacturing.

Investor Perspective: Navigating a Changing Policy Landscape

The workshop also provided an opportunity to gain key insights on investors’ perspectives. Former mining multinational executives and mining lawyers shared their experiences, and the following key points emerged:

Complying with strict ESG standards: Participants noted the general perception that conducting business in Africa is riskier than in other regions. Thus, it is worth asking how this perception influences an investor’s mindset. African governments should be conscious of the expectations and pressures placed on investors. Legal counsels representing investors’ interests are obligated to negotiate positions that the investors’ country of origin will support. For instance, the European Union (EU) has strict ESG standards that are being exported to African countries. Consequently, investors domiciled in the EU are required to report on ESG performance annually, a consideration that often influences negotiations. African governments should—and do have the power to—create an enabling and facilitating environment for investments by avoiding policy inconsistencies. Investors look for stability in their contracts. Sudden changes to the tax code, for instance, can make a project completely unprofitable. Equally, investors cannot be successful in a country without respecting what it provides and should support broader development on the sidelines of their work, via philanthropy and investments in local communities.

Understanding various appetites for risk: Participants also noted a difference between mining investors from Western countries and those from China, particularly in their understanding and appetite for risk. Chinese companies appear to have a higher risk appetite (in other words, Chinese state-owned enterprises backed by state capital are more able than their Western counterparts to undertake mining projects in countries that present high political and security risks).5 As such, African governments need to have a better grasp of the differences in how investors view risk. One important way that investors mitigate risk is by analyzing the entire value chain. Beyond this technical analysis, it is necessary for investors to bring host communities on board to ensure they get value out of mining project and to avoid ESG risks.

Defining “criticality”: Participants also highlighted the need for a better understanding of how investors define what mineral is “critical.” Although a particular mineral resource may not be “critical” for the manufacturing of clean energy technology hardware, it may still be regarded as “critical” to an investor due to the resource’s position in the company’s overall assets or its revenue generation potential. Participants further noted that talking about “critical” minerals could distort the conversation, as it falsely suggests that criticality is universal. It is thus important to ask each investor why they deem specific minerals as “critical.” African governments must understand these varying definitions of criticality from their perspectives and those of investors.6

Realizing that details matter: There is a long-held perception that African governments are not sophisticated enough and that they do not sufficiently recognize and respond to the dynamics of the global geopolitical landscape and their own vulnerabilities. In noting this, participants stated that specificities regarding these dynamics matter, since investors bring a refined set of specific wants to the negotiation table. Participants highlighted that African governments should include clauses that allow for renegotiation, as well as define what is local content, as it can be very fluid. Moreover, governments should do their due diligence in researching the investor’s activities and enquire what they have negotiated elsewhere.

Considering time horizons: Some investors have a long-term view given the length of time it takes to go from mineral prospecting to actual project development—up to a decade in some cases. Meanwhile, some government negotiators have a shorter-term view due to the pressures of electoral politics. Culturally attuned translators could play a key role here, as they could help elucidate what is being said on the other side of the negotiation table. Contracts negotiated with the incumbent government may be seen differently by the successor government. Furthermore, given that negotiations and project setup and implementation takes time, contracts must be made to look good to potential successor governments as well.

Structuring negotiations: It is also essential to understand how negotiations are structured from the investor’s perspective. Several participants highlighted that investors want negotiations to be structured in a way that minimizes risk and maximizes reward. This way, investors can recapitalize and sustain business. There is a stereotype that African governments are not skilled in contract negotiation. The general perception is that there is some kind of imbalance between investors and governments. Consequently, there is often some tension at the negotiating table. Negotiations need to be structured to build trust in the process, in order to create sufficient understanding of both perspectives, mobilize the right skill sets, and foster respect for what those involved bring to the table. It is important for governments to integrate the expertise that is already present in their country.

There is never a perfect outcome between the investor and the government/entity in mining negotiations. There will always be some tension during negotiations, but tension can be used to ensure a good return on investment for both parties. For governments, it is important to anticipate future demands and profits and to ensure that the host state where the mine is located will get an equitable share of the increasing profit. For investors, it is important to build trusting relationships and to use culturally attuned translators so that the two parties fully understand one another. Abilities and skills on both sides need to be developed to create a conducive culture for balanced negotiation. Shifts in the balance of power should be recognized and assimilated, as some shifts could positively change the nature of negotiations going forward.

Drawing Lessons From Indonesia’s Experiences

The workshop also included a fireside chat with Muhammad Lutfi, the former minister of trade of the Republic of Indonesia. The discussion focused on Indonesia’s efforts to maximize the benefits of its strategic minerals, particularly in achieving domestic value addition for nickel and bauxite. The discussions focused on the key elements of Indonesia’s different approach to engaging and negotiating with foreign investors and how it yielded tangible results. Most importantly, the former minister shared insights on recent experiences that may be useful for African countries.

Implementing export restrictions to encourage domestic processing while being pro-business: For more than three decades, Indonesia was trapped in a vicious cycle of extraction and low-value processing of nickel and bauxite ore until a decision was reached to make tangible progress in automobile manufacturing. In 2014, then Indonesian president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono banned the export of raw nickel (used for critical applications in stainless steel, construction and industrial purposes, and lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles) and bauxite ore, with the aim of increasing value added while slowing the unsustainable extraction rate in response to commodity booms and encouraging foreign investment in metal smelting.

To reinforce this policy in 2019, current President Joko Widodo finally put a stop to exporting unprocessed bauxite and nickel. To do so, Widodo harmonized 2,900 laws to make the environment more welcoming for industry. The underlying objective was to make Indonesia appear pro-investment and pro-business. This move attracted criticism both inside the country and externally about the ban’s potential limitations and lack of efficiency, but Indonesia pressed ahead. Setting a development target was equally important: in the case of Indonesia, it was about avoiding the middle-income trap, that is, when lower growth follows after a country rapidly goes from low-income to middle-income levels—a transition that is fueled by cheap labor, basic technology catch-up, and the reallocation of labor and capital from low-productivity sectors like traditional agriculture to export-driven, high-productivity manufacturing.7

The export ban produced different results for bauxite and nickel. The initial bauxite ban in 2014 led to importers capitalizing on other markets—notably contributing to an over twenty-one-fold increase in Chinese imports of Malaysian bauxite.8 Whereas the nickel ban (initiated in 2014 and reinstated in 2020 after a brief lapse in enforcement) has been more successful because of Indonesia’s controlling share of 40.2 percent of the world’s nickel.9 With nowhere else to turn for the raw material, foreign companies have been forced to pay a premium, investing in processing and refining activity. The ban resulted in a shift in the composition of Indonesia’s exports to higher-value nickel products, increases in downstream production, and more foreign investment in the country following the ban.10 On the previously undeveloped nickel-endowed island of Maluku, nickel refining expanded the province’s economy by 29 percent in 2022 alone.11 Indonesia’s strategy could be viable in the DRC (74 percent of the world’s production of cobalt),12 Mozambique (12 percent of the world’s production of graphite),13 and Madagascar (9 percent of the world’s production of graphite)14—countries that all contribute a significant amount to the global market.

Developing a strong trade bench: The fireside chat participants discussed the need for effective and dynamic trade agreements with partner countries. If African countries do not have such trade agreements in place by the time a mining processing or refining project is ready, there will be no market to sell their products to. Indonesia also needed to harness expertise to be able to defend itself at the World Trade Organization’s Dispute Settlement Body when mining companies and their host governments reported Indonesia.15 Such defense cases are usually expensive and demanding on developing countries.

The Indonesian experience showcases that although there is no “one size fits all” model, a key element includes setting a target as part of a broader economic development strategy to avoid the middle-income trap, leverage and utilize natural resources, and steer clear of paths that have not produced benefits. Another central element includes developing standards by building the right regulatory framework and engaging in a race to the top (not to the bottom). Bolstering negotiation power, analytical skills, and technical capacity for production could open the way for African countries to shape and influence the domestic and global markets.

Bridging the Capacity Gap

The final session of the workshop was dedicated to identifying expertise gaps in mining negotiations and brainstorming ways to bridge the gaps. Participants included representatives from regional organizations, multilateral development banks, and nonprofits, as well as legal experts. The discussion highlighted several key points:

Increasing leverage in future negotiations: Imbalances between governments and investors in terms of information and data, technical capacity, and financial resources often undermine the negotiation position of African countries. Panelists explored how external experts (for example, lawyers, trade and contract negotiators, and representatives of nongovernmental organizations) could help address these capacity imbalances and increase African countries’ leverage in future negotiations. They also discussed whether existing norms and governance frameworks were sufficient for the new wave of strategic minerals investments in African countries. The panelists underscored that African governments should mobilize both external and in-house expertise to increase capacity, while ensuring that knowledge is transferred from senior officials to younger officials.

Increasing exposure and transparency: Participants discussed how African governments could build additional capacity via exposure to previous mining negotiations, learning, and training. This exposure could prepare governments to handle the complexity of contracts. A clear road map is also needed: they should take time to collect detailed data, do their due diligence on potential risks with the contract, and use bargaining power. It is important for negotiators to be mindful of the quality of the negotiation process itself rather than just the end result and to strike a balance between short- and long-term gains. The inclusion of civil society and think tank representatives, academics, and other policy experts in the process could provide additional expertise and generate better win-win outcomes. This inclusion of nongovernmental experts could also increase transparency. It is equally important to tackle corruption surrounding the negotiation process and avoid initiating negotiations prior to elections. African governments should ensure a transparent process and publish the terms of negotiation so that oversight institutions can assess the alignment of conduct with the proposed objectives.

Increasing knowledge and capacity on engaging with Chinese entities: Participants also discussed deals with Chinese companies who lead mineral extraction in several African countries. They noted that Chinese overseas companies have a high-risk appetite because they are often backed by the Chinese government.16 Generally, Chinese companies have been associated with high levels of chemical pollution, particularly within China itself. This partly explains why Chinese companies adapt very quickly to low environmental standards abroad. African governments should give just as much attention to the social and environment components of deals as they do to the financial component. African governments should increase capacity at home to constructively engage with China by, for example, sending professionals to China to understand Chinese laws, policies, rules, and business culture. Several African negotiators cannot speak Mandarin or directly negotiate with Chinese stakeholders. They should learn the language or assign internal or hire external experts that have a better understanding of Chinese negotiation culture.

Seizing the moment: There was a general consensus that African negotiators should seize this moment to correct some of the wrongs from past mining practices. For instance, China has a “strategic resource” category that it reviews every five years; African countries could emulate that process and define their own categories of what is “critical.”

Operating at the continental level: Finally, participants explored the roles that African regional organizations and international organizations could play during negotiations. They stressed the need for the implementation of the African Mining Vision across the continent to address the continent’s existing concerns with contract negotiation and to ensure sustainability by operating at the continental level.17 The workshop panel cited the necessity of organizations such as the African Minerals Development Centre in assisting with the negotiation process to further ensure its transparency.18

“Win-Win” for Whom and for What?

The workshop concluded with emphasizing a few important broad observations. First, having patience despite a competitive environment marked by geopolitical rivalries is crucial. Second, to define African countries’ and investors’ interests, it is important to bring together all actors at the local level to discuss the best potential value chains. Questions should be asked around how to cultivate a “win-win” strategy, especially within the context of current geopolitics. A good starting point would be defining who is “winning” what and how.

The balance of power between African governments and investors is changing. Increasing African bargaining power implies bargaining more collectively; African governments must understand the criticality of this context and identify and define their redlines and non-negotiables.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks all the workshop participants for a rich and meaningful group discussion. The author also thanks the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Africa Program for managing the workshop’s logistics, as well as the 2024 Investing in African Mining Indaba conference for providing the event space.

Notes

1 “The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions: Executive Summary,” International Energy Agency, accessed May 29, 2024, https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions/executive-summary.

2 Magnus Ericsson, Olof Löf, and Anton Löf, “Chinese Control Over African and Global Mining—Past, Present and Future,” Mineral Economics 33 (2020): 153–181.

3 Folashadé Soulé, “What a U.S.-DRC-Zambia Electric Vehicle Batteries Deal Reveals About the New U.S. Approach Toward Africa,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, August 21, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/08/what-a-us-drc-zambia-electric-vehicle-batteries-deal-reveals-about-the-new-us-approach-toward-africa?lang=en.

4 Susannah Fitzgerald, Phesheya Nxumalo, and Thomas Scurfield, “Deals Without Details: Exploring State-State Mining Partnerships and Their Implications,” NRGI blog post, February 6, 2024, https://resourcegovernance.org/articles/deals-without-details-exploring-state-state-mining-partnerships-and-their-implications.

5 Katy N. Lam, Chinese State-Owned Enterprises in West Africa: Triple-Embedded Globalization (London and New York: Routledge, 2017).

6 Isabelle Ramdoo, Grégoire Bellois, and Murtiani Hendriwardani, “What Makes Minerals and Metals ‘Critical’? A Practical Guide for Governments on Building Resilient Supply Chains,” Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development, May 2024, https://www.igfmining.org/resource/what-makes-minerals-and-metals-critical/.

7 Greg Larson, Norman Loayza, and Michael Woolcock, “The Middle-Income Trap: Myth or Reality?,” World Bank Malaysia Hub, March 2016, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/965511468194956837/pdf/104230-BRI-Policy-1.pdf.

8 Andy Home, “Bauxite and the Limits of Resource Nationalism,” Reuters, March 29, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSL6N0WT1TS/.

9 Eri Silva, “Indonesian Nickel Production Dominates Commodity Market,” S&P Global, February 6, 2024, https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/indonesian-nickel-production-dominates-commodity-market-80242322.

10 David Guberman, Samantha Schreiber, and Anna Perry, “Export Restrictions on Minerals and Metals: Indonesia’s Export Ban of Nickel,” Office of Industry and Competitiveness Analysis, United States International Trade Commission, February 2024, https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/working_papers/ermm_indonesia_export_ban_of_nickel.pdf.

11 Eko Listiyorini and Norman Harsono, “Nickel Shows Indonesia How to Escape the Middle Income Trap,” Bloomberg, February 24, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-25/indonesia-has-a-plan-to-double-wealth-based-on-its-nickel-boom?sref=QmOxnLFz.

12 “How Critical Minerals Can Unlock a Cleaner Energy Future,” International Energy Agency, accessed May 29, 2024, https://www.iea.org/topics/critical-minerals.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 “DS592: Indonesia — Measures Relating to Raw Materials”, World Trade Organization, last updated December 2022, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds592_e.htm.

16 Lam, Chinese State-Owned Enterprises in West Africa.

17 “Africa Mining Vision,” African Union, February 2009, https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/30995-doc-africa_mining_vision_english_1.pdf.

18 “African Minerals Development Centre: About,” African Union, accessed May 29, 2024, https://au.int/en/amdc.