LDCs – We Must Ensure That Low Carbon Transitions Don’t Harm Poor Countries

By Kingsley Ighobor

Paul Akiwumi, Director of UNCTAD’s Division for Africa, says LDC5 Conference in Doha is an opportunity to begin to tackle the problem

Political leaders, the private sector, parliamentarians, development experts and young people from around the world will gather in Doha, Qatar, during 5 -10 March 2023, to once again discuss ideas on how to tackle development challenges bedeviling the Least Developed Countries (LDCs).

It will be the Fifth UN Conference on the Least Developed Countries. The UN touts the Doha event as “a once-in-a-decade opportunity to accelerate the sustainable development in places where international assistance is needed the most.”

There are 46 LDCs globally, 33 of these are in Africa.

Poverty-related issues will take centre stage in Doha and the focus will be on how to transform economies with the help of international trade, structural transformation and science and technology.

Continuing from the COP27 climate talks in Egypt last November, African delegates in Doha will likely continue their advocacy for finance for loss and damage. Africa’s case is straightforward: the continent contributes the least to greenhouse gas emissions but suffers the brunt of climate change.

Yet, from beneath the usual canvassing for support for Africa’s development may pop up an issue that is yet to gain currency in development conversation, namely the unintended consequences of low-carbon transition for LDCs.

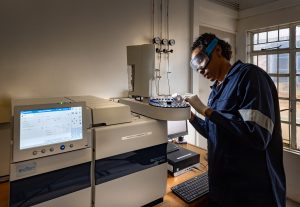

The issue is the focus of the latest UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)’s signature annual LDC Report titled The low-carbon transition and its daunting implications for structural transformation.

Released in November 2022, the report maintains that LDCs are facing “additional headwinds because of the environmental policies of their trade partners.”

It warns that trade partners’ policies targeting the carbon emissions generated in the production of exported goods could hit LDC economies.

Polluting industries could be displaced “out of developed countries and into LDCs” because the countries transitioning to low-carbon emissions want to meet their climate commitments.

Unintended consequences

In an interview with Africa Renewal, Paul Akiwumi, Director of UNCTAD’s Division for Africa, elaborates on the report: “The intention to deal with carbon emissions using trade policies is a good idea, but there are unintended consequences,” he says.

“What I mean is that LDCs are in a commodity-dependent trap, and they are trying to diversify and add value to the products.

“But at the same time the world is trying to deal with the climate agenda and tackle greenhouse gas emissions using trade policies.”

Unlike the advanced economies, low carbon transition in commodity-dependent countries is difficult because of a weak industrial base. Therefore, developed countries taxing companies that import commodities from Africa will hurt the continent’s economies.

“Take sectors like fertilizer, steel and cement. You say you want to know how much carbon is associated with any imports coming into the European Union, how much carbon emission was created as a result of fertilizer or steel being manufactured in Mozambique and then trying to link it to carbon tax–that’s the direction we are heading.

“The EU has Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism,” says Mr. Akiwumi. The EU says its aim is to “put a fair price on the carbon emitted during the production of carbon intensive goods that are entering the EU, and to encourage cleaner industrial production in non-EU countries.”

LDCs – 33 African countriesAngola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Togo, Uganda, Tanzania and Zambia.

UNCTAD’s annual LDC Report titled: The low-carbon transition and its daunting implications for structural transformation, released in November 2022 says LDCs are facing “additional headwinds because of the environmental policies of their trade partners.”

The intention to deal with carbon emissions using trade policies is a good idea, but there are unintended consequences. LDCs are in a commodity-dependent trap, and they are trying to diversify and add value to the products. But at the same time the world is trying to deal with this climate agenda and tackle greenhouse gas emissions using trade policies.

US and Japan

America and Japan are thinking of establishing a similar mechanism, says the UNCTAD director.

“What it means is that the LDCs that export to EU are going to become less competitive because the importer in Europe will tell the exporter in Mozambique ‘you tell me how much carbon was emitted to make a product.”‘

“On top of that, the imposition of carbon credits will be additional cost on the products.”

He laments that the LDCs lack the technology currently to reduce carbon emissions in key exports to make them competitive in the global marketplace.

“So, many LDCs will simply just export the raw commodity–the lithium, the cobalt, the copper– the way they’re doing it now because they cannot add value to them.”

Mr. Akiwumi is pained that “we talk about leaving no one behind, but we will be leaving LDCs further behind because they will not have the necessary technology. They don’t have it now. They will not have it in the near future.”

Polluting companies

On polluting industries being displaced out of developed countries and moving to LDCs, a highlight of the UNCTAD report, Mr. Akiwumi calls it “carbon dumping,” which must concern the LDCs.

He explains: “By 2030-2035, most European new vehicles will be electric. So, we will be buying second-hand cars in Africa that use petrol or diesel. That is the beginning of carbon dumping. Without a doubt, I see it with vehicles straight away.”

Solutions

It’s a conundrum: that countries are encouraged to transition to low-carbon emission, yet the transition could hurt a continent that is already reeling from the devasting effects of climate change. Are there solutions?

Yes, says Mr. Akiwumi. “First, is for the developed countries to recognize this problem,” he stresses.

“Second, they must be able to provide financial support for the LDCs to address this issue. If, for instance, there are new technologies that reduce the CO2 emissions in steel production, they must be able to help LDCs get that technology.”

Third, he says local companies must take some responsibility. “We need national firms that are embracing and absorbing the relevant technology. It cannot be only the international firms because if the international firms leave, the country is in a mess.”

Fourth, Mr. Akiwumi maintains that “LDC economies must be careful not to stay in the commodity-driven model. The green structural transformation to produce batteries, solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles is ongoing.

“The demand for hydrocarbon fuels will be going down and the value will be going down as well. So, you’re going to have stranded assets in these countries if the value depreciates so much or if there is no value over time.”

LDCs are going to be more or less an African issue. And what is critical for Africa is to make the African Continental Free Trade Area work. Africa needs to trade within itself.

Mr. Akiwumi says countries like Zambia and others need to adapt. “Add value to copper; manufacture the copper wires needed in Europe for charging cars.”

The fifth solution is an increase in intra-African trade. “LDCs are going to be more or less an African issue. And what is critical for Africa is to make the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) work. Africa needs to trade with itself.

“The AfCFTA has many mechanisms to enhance intra-African trade, such as the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System.” Also known as PAPSS, this is a platform that facilitates instant cross-border payments in local currencies between countries, and could save Africans $5 billion annually, according to the Afreximbank.

The last solution is for African governments to enact policies that help the domestic private sector because, in many instances, “many policies do not really help the domestic private sectors; they focus on the international private sector.”

At Doha, Mr. Akiwumi expects countries to pay attention to key elements of UNCTAD’s LDC report.

The unintended consequences of low carbon transition are real. “We hope that somebody in Doha will recognize them and say these are the things we need to do to address the situation.”

Share this content: