Africa’s artisanal miners may benefit from global renewables push

What’s the context?

Entrepreneurs, victims, or criminals? Artisanal miners could reinvent themselves as the world flocks to Africa’s critical minerals

Hundreds of informal miners in South Africa faced a stalemate in recent months after police cut off food and water to an illegal goldmine shaft in November: stay and starve, or emerge above ground and face definite arrest.

The move was part of an operation launched by South Africa’s police in 2023 to stop illegal mining.

The conundrum left at least 78 dead, and some 250 others pushed to the point of emaciation when they were rescued in January, following a court order.

South Africa’s zama-zamas, meaning “hustlers” in Zulu slang, are among millions of artisanal miners across Africa seen either as victims of an unequal mining sector — where companies take all the profit — or criminals dodging the law.

As the world shifts towards renewable energy, fueling appetite for Africa’s critical minerals like cobalt and lithium, will informal miners be part of the new value chain or be sidelined by bigger corporate players?

What is artisanal mining and where are the Africa hotspots?

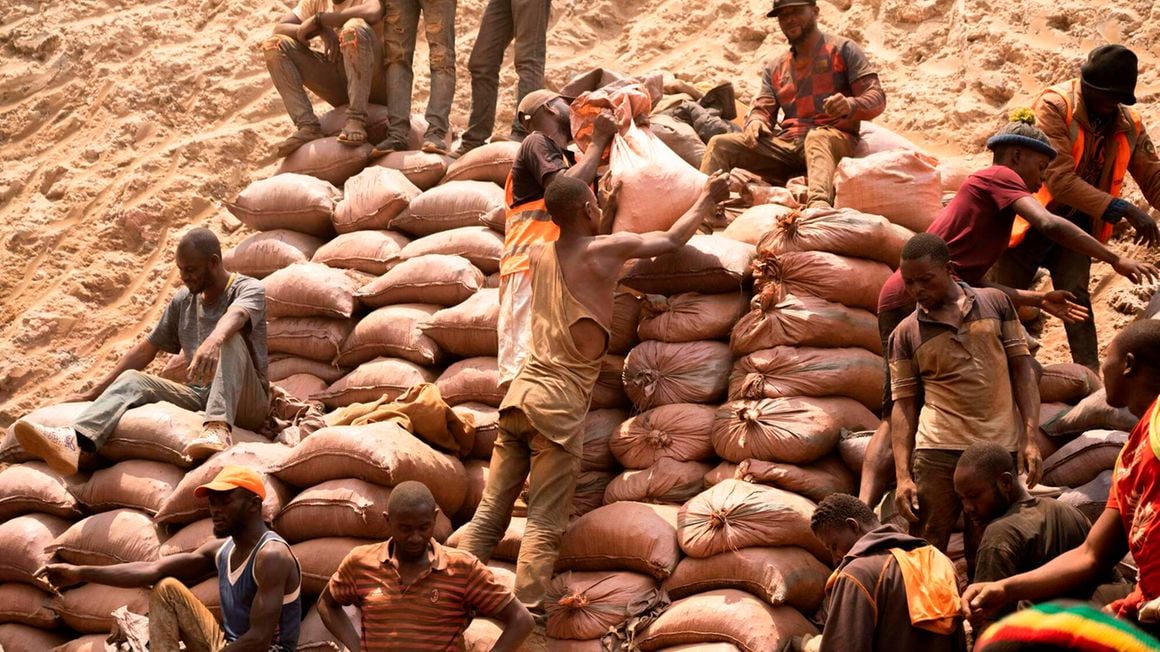

Artisanal and small-scale mining, known as ASM, refers to mining carried out by individuals or small groups outside of the formal mining sector using basic equipment like picks and shovels, according to the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) think tank.

Such mining without licenses or permits is generally considered illegal in Africa.

At least 90% of the world’s artisanal miners work informally, without the necessary licenses or permits required by law, according to international non-profit Pact.

Small-scale mining is common across Africa, including in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ghana, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Zambia, Tanzania and Burkina Faso, according to the IIED.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, ASM employs an estimated ten million people in rural areas, according to the World Bank. The livelihoods of up to 270 million people depend on artisanal mining globally, according to NovaAfrica research centre.

In the DRC, where 70% of the world’s cobalt is found, it is estimated that there are some 1.5 million artisanal miners, according to The Fair Cobalt Alliance.

The DRC is also the site of complex criminal syndicates involving child labour, smuggling and collusion with gangs and political leaders, according to the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) think tank.

The exact number of artisanal miners in each country is difficult to quantify as many artisanal miners work informally and are not officially registered.

With global pledges to move away from planet-heating industries like coal production, the demand for ‘net zero’ minerals is set to triple by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency.

The World Economic Forum estimates this demand will grow by 500% by 2050.

With approximately 40% of these critical minerals found in Africa, a global rush to mine and export these resources is underway.

Why is artisanal mining controversial?

When unregulated, artisanal mining can go hand-in-hand with illegality, deforestation, water pollution, soil contamination and labour exploitation.

But it also contributes to the economy through informal job creation and industry researchers believe that through formalising ASM, artisanal miners can become bigger players in Africa’s critical mining sector going forward.

Human rights abuses need to be cut out of supply chains, not the artisanal miners, according to Global Witness human rights charity.

The charity points out that large-scale mining (LSM) is also associated with environmental degradation, corruption, and human rights abuses.

Some rights groups, such as the WoMin eco-feminist group that monitors environmental abuses across the continent, note that artisanal mining often supplemented women’s agricultural activity in precolonial Africa.

Through assisting women and artisanal miners with capital, market access, safer mining equipment and health and safety awareness campaigns, ASM can be a source of much-needed employment for those excluded from the resource value chain, according to a WoMin report.

Formalising the sector through affordable and simple licensing agreements could help create safer environments and fairer labour practices, The Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development (IGF) said.

The recent IGF report also suggested ring-fencing critical mineral sites and issuing licences to ASM operators to better regulate and support these small-scale miners in this new wave of mineral demand.

(Reporting by Kim Harrisberg; Editing by Ana Nicolaci da Costa.)

Share this content: